FOOD BYTES IS A (ALMOST) MONTHLY BLOG POST OF “NIBBLES” ON ALL THINGS CLIMATE, FOOD, NUTRITION SCIENCE, POLICY, AND CULTURE.

It is hard to find the time to read, let alone write about what you read. One of the things about reading scientific literature is that you have to weed through many journals’ tables of contents to find the nibbles and nuggets that are worth your time. Sometimes, you get lucky and find some gems; other times, you don’t get further than the abstract. Regardless, if you don’t have LinkedIn or X, spoon-feeding your biased and “like-minded lemur” content, the never-ending search for quality papers is laborious and time-consuming.

Enter documentaries and podcasts. I find myself more and more listening to them to get a synthesis of a topic or a deep dive into an issue or scientific discovery. There is no shortage of food podcasts, but most focus on cooking and gourmandery. But a few goodies discuss the politics of food and the history of food. I try to add them to the Resource section of The Food Archive. I found this particular episode of the podcast, “What You’re Eating,” fantastic on the confusion of egg labels. The host lays out the issues and clarifies where your eggs come from and how to understand the labels on those confusing cartons better.

Two food documentaries worth the watch are Poisoned and How to Live to 100, Wherever You Are in the World. Let’s take Poisoned first, about how “unsafe” the U.S. food supply is, although often touted as being one of the most secure. The documentary starts with the contaminated burgers from Jack in the Box, which killed and sickened a slew of people. After lawsuits and regulations, getting sick from E. coli-contaminated hamburger meat is hard now. It shows that it works once governments can set their mind to something and put in strict and enforced regulations. Enter vegetables. After watching the show, I am not sure I will ever eat romaine lettuce again…much of it is grown right next to concentrated animal feed operations (where beef is raised in the U.S.). The manure runs off into waterways, and the water from those said waterways irrigates the nearby lettuce crops. And then bingo! You’ve got severe contamination issues. It is worth watching to understand how food is produced in this country, how it is regulated, and how you can be safer with food in your kitchen.

How to Live to 100 is hosted by Dan Buettner, who wrote Secrets of the Blue Zones. He has been studying why, in some places, people live such long lives – sometimes beyond 100 years. He travels to Okinawa, Japan; Ikaria, Greece; Sardinia, Italy; Nicoya, Costa Rica; and Loma Linda, California — where more people live significantly longer than average. He summarizes some of their secrets to longevity into four basic mantras. Keep in mind these populations all get to their winter years in different, contextualized ways, and it is never that straightforward why someone lives a long life and others die too early. Dan argues these four lifestyle changes help:

Make movement a habit

Have a positive outlook

Eat wisely

Find and connect with your tribe

There are a lot of valuable lessons in this documentary (sans Dan showing himself riding his bike for 1/3 of the docuseries. Why do documentarians always have to show themselves so much? I digress…). One lesson is that no matter how long you live, you can live your best life and one of high quality. A lot of that centers around food. And wine. Yay!

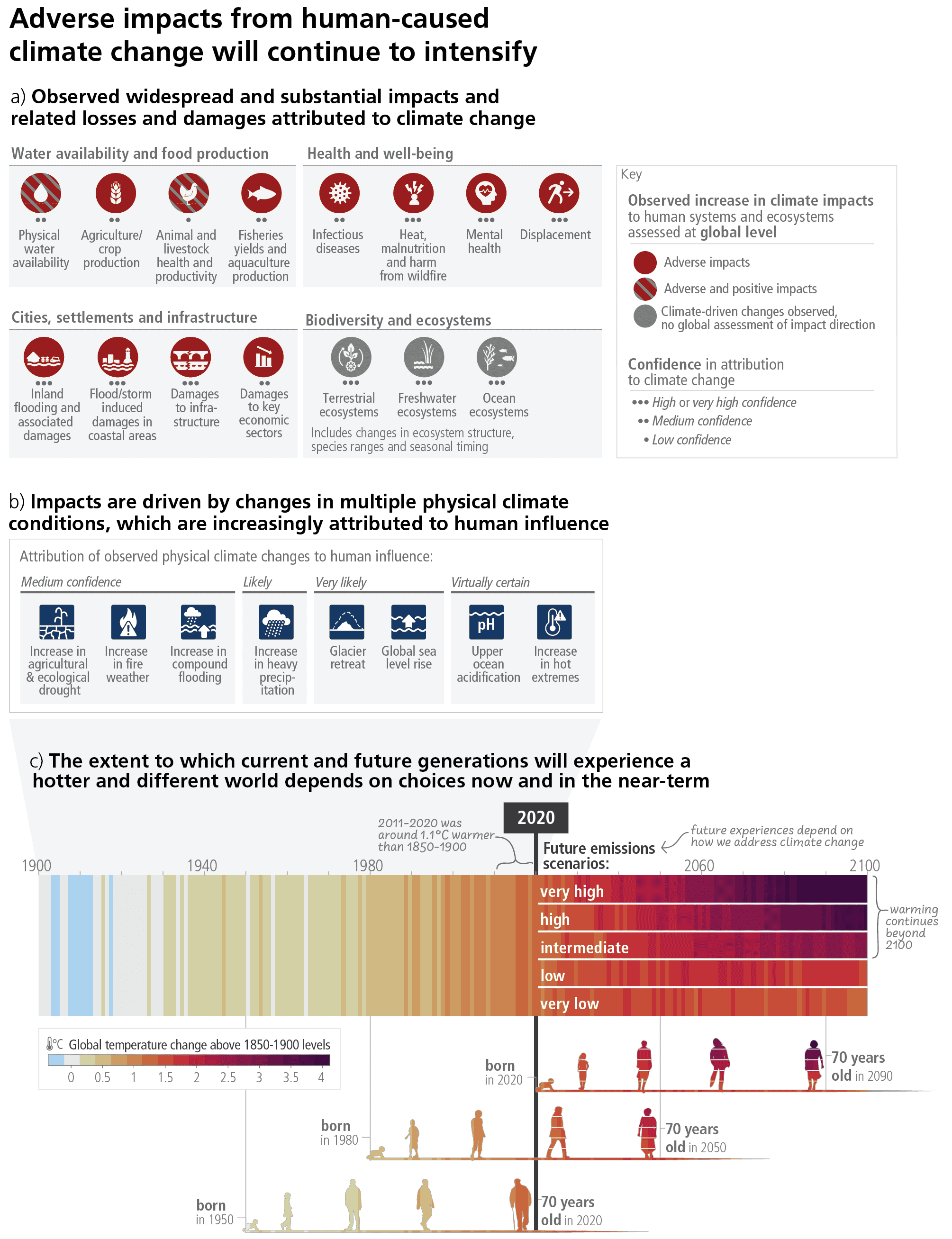

The NY Times Magazine had two fantastic articles last week. David Wallace-Wells wrote a piece on the financial responsibility for climate change and how difficult it is to figure out the historical tally of damage. The price of historical emissions and removing carbon would cost $250 trillion. The U.S. alone has accrued a climate debt of $2 trillion. By 2100, $100 trillion. This shows how daunting it will be to turn around the damage we have done and will continue to do without serious action on climate change.

Another NY Times Magazine article focuses on young migrant kids from Central America who work night shifts in slaughterhouses – a dangerous, low-paying job – with very little compensation or legal status. They are often too tired when they get to school after working long, laborious hours all night, and often, they get maimed, injured, or exposed to terrible toxins that stay with them for a lifetime. It is a tragic story but so important to read to understand why younger kids and teens are trekking up to the U.S., what they face along the way and when they get here, and the fine line to ensuring their freedom. While it seems we have come a long way from the days of The Jungle, written in 1906 by Upton Sinclair of the Chicago slaughterhouses, this article makes you pause. Your heart will break for Marcos Cux.

And for some self-promotion, my team and colleagues published a few papers in the last six months that may be of interest to Food Archive readers:

Challenges and opportunities for increasing the effectiveness of food reformulation and fortification to improve dietary and nutrition outcomes: This article is about how reformulation and fortification face numerous technical and political hurdles for food manufacturers and will not solve the issues of increased consumption of ultra-processed foods. You can’t make junk food healthier at the end of the day…

Harnessing the connectivity of climate change, food systems, and diets: Taking action to improve human and planetary health: This paper presents how climate change is connected to food systems and how dietary trends and foods consumed worldwide impact human health, climate change, and environmental degradation. It also highlights how specific food policies and actions related to dietary transitions can contribute to climate adaptation and mitigation responses and, at the same time, improve human and planetary health. While there is significant urgency in acting, it is also critical to move beyond the political inertia and bridge the separatism of food systems and climate change agendas currently existing among governments and private sector actors. The window is closing and closing fast.

A global view of aquaculture policy: This article shows that government policies have strongly influenced the geographic distribution of aquaculture growth, as well as the types of species, technology, management practices, and infrastructure adopted in different locations. Six countries/regions are highlighted – The EU, Bangladesh, Zambia, Chile, China, USA, and Norway. These case studies shed light on aquaculture policies aimed at economic development, aquaculture disease management, siting, environmental performance, and trade protection.

Riverine food environments and food security: a case study of the Mekong River, Cambodia: Rivers are critical, but often overlooked, parts of food systems. They have multiple functions supporting the surrounding communities' food security, nutrition, health, and livelihoods. However, given current unsustainable food system practices, damming, and climate change, most of the world’s largest rivers are increasingly susceptible to environmental degradation, with negative implications for the communities that rely on them. Rivers are dynamic and multifaceted food environments (i.e., the place within food systems where people obtain their food) and their role in securing food security, including improved diets and overall health.