FOOD BYTES IS A (ALMOST) MONTHLY BLOG POST OF “NIBBLES” ON ALL THINGS CLIMATE, FOOD, NUTRITION SCIENCE, POLICY, AND CULTURE.

“All of my work is directed against those who are bent on blowing up the planet.” —William S. Burroughs

That just about summarizes it for me. I can’t even begin to fathom what the world will look like here in the U.S. come Jan 1st 2025 (along with the other 4.2 billion people voting for their democracy this year), but I will continue to hang onto the small glimmers of hope for a humanity that doesn’t want to watch the world burn. On a lighter note, let’s get into some food bytes.

Lately, I have been listening to a lot of podcasts while walking to work. There are a few that are worth a listen. Although an older podcast, Everything is Alive is witty. It brings to life everyday objects. For you foodies out there, Louis the Can of Soda (“That's my evaluation of humanity. A chronic search for potency”), Jes the Baguette, and Vinnie the Vending Machine are pretty hilarious. I also listened to the BBC Food Programme’s Herb and Spice Scam. Yes, your oregano is full of olive leaves…and the BBC Food Chain’s Why We Love Dumplings. First off, the host, Ruth Alexander, has the most soothing voice. She really should do some nighttime readings on the Calm app. Second, dumplings hold a unique place in society. Every country/culture has them as part of their staple cuisine: gyozas, wontons, ravioli, pierogis, samosas, khinkali, and empanadas, to name a few (see the photo of these Cuban varietals I recently took at the Isla Diner in Hoboken). Just delish.

As I have mentioned in past blogs, there is the 6-part Barbeque Earth by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace is just outstanding. I highly recommend it. Stay tuned for more podcasts by Ambrook Research’s The Only Thing That Lasts podcast on America’s farmlands, indeed a very precious resource. The first episode wondered if farmland is running out in the U.S., spurred by fears that Bill Gates is gobbling it all up (he owns about a quarter of a million acres of it). The second episode dives into the creation of U.S. farmland.

As far as major media stories go, this long read by the New York Times on India’s sugar cane fields and their impacts on families, particularly women and children, is disturbing and tragic. Worth the read before you open that next can of ice-cold Coke.

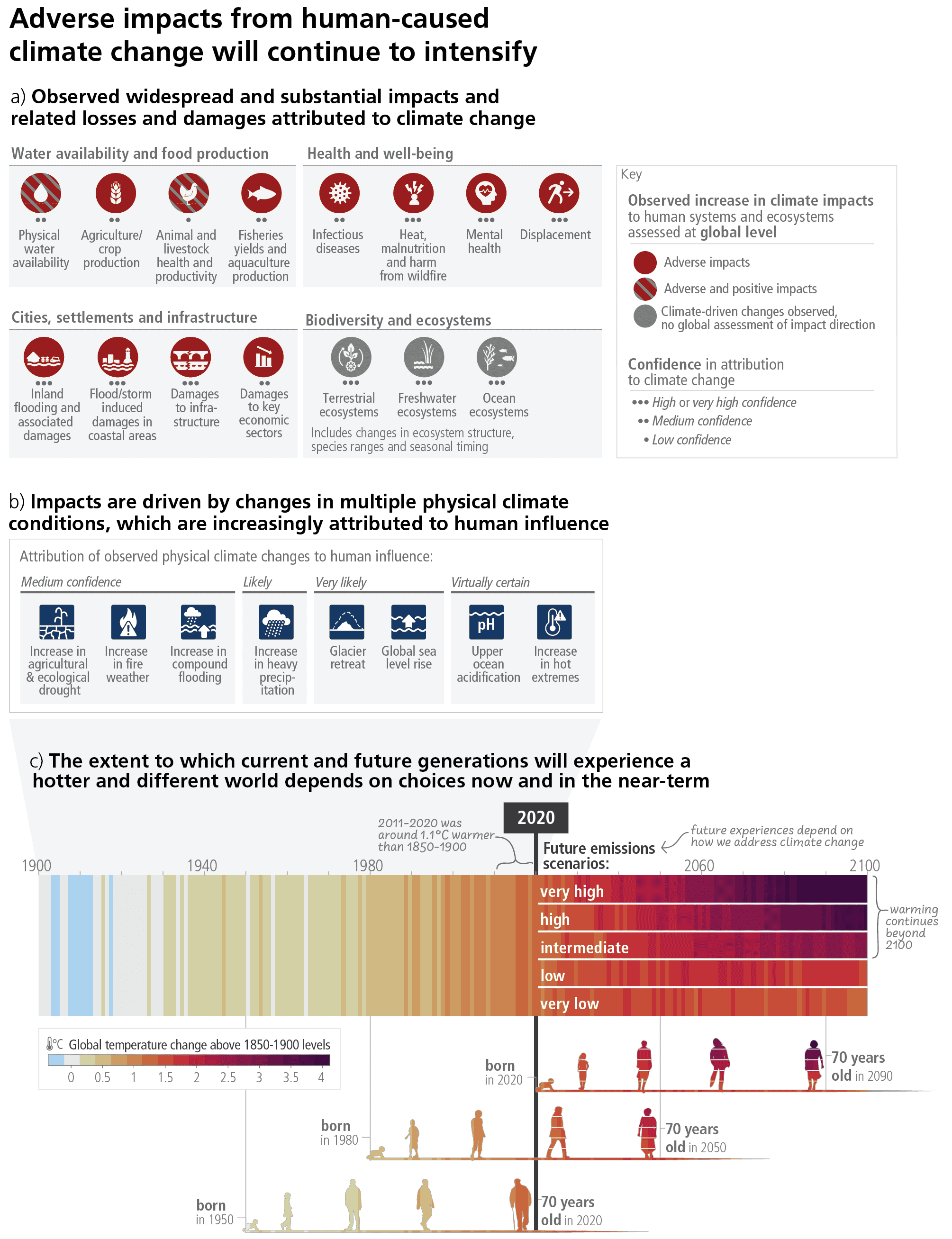

Lately, many reports have pulled together evidence on the links between climate and nutrition. Per my usual spiel, there has been so much research over decades showing the various links between climate change, variability, extreme weather events, and deleterious nutrition outcomes, but it sometimes takes a large-scale report to draw attention to the topic. Here are just a handful that have come out in recent months:

Emergency Nutrition Network’s report: Exploring new, evolving and neglected topics at the intersection of food systems, climate change and nutrition: a literature review.

Stronger Foundations for Nutrition’s report: An Evidence Narrative on Climate Change and Nutritious Foods. They also put out a database of climate-nutrition evidence. I was happy to see our team listed with other great researchers, such as Marco Springmann, Sam Myers, Andy Haines, and Matthew Smith.

ANH Academy’s evidence map: Intersections of climate change with food systems, nutrition, and health: an overview and evidence map.

Speaking of food and climate reports, a few are worth your time.

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) released a report in the last two weeks titled The Unjust Climate: Measuring the impacts of climate change on the rural poor, women, and youth. The report highlights how the climate crisis is particularly unjust for rural women. This statistic stood out: A 1° C increase in long-term average temperatures is associated with a 34% reduction in the total incomes of female-headed households relative to those of male-headed households. Extreme weather events also undermine the incomes of the female-headed households relative to those of male-headed households. Check out this figure on the right that shows just one additional day of extreme temps or precipitation is associated with 1.3% and 0.5% reduction in income for women. This may not seem like a lot, but this reduction translates to an annual income loss of 8% with heat stress and 3% with floods.

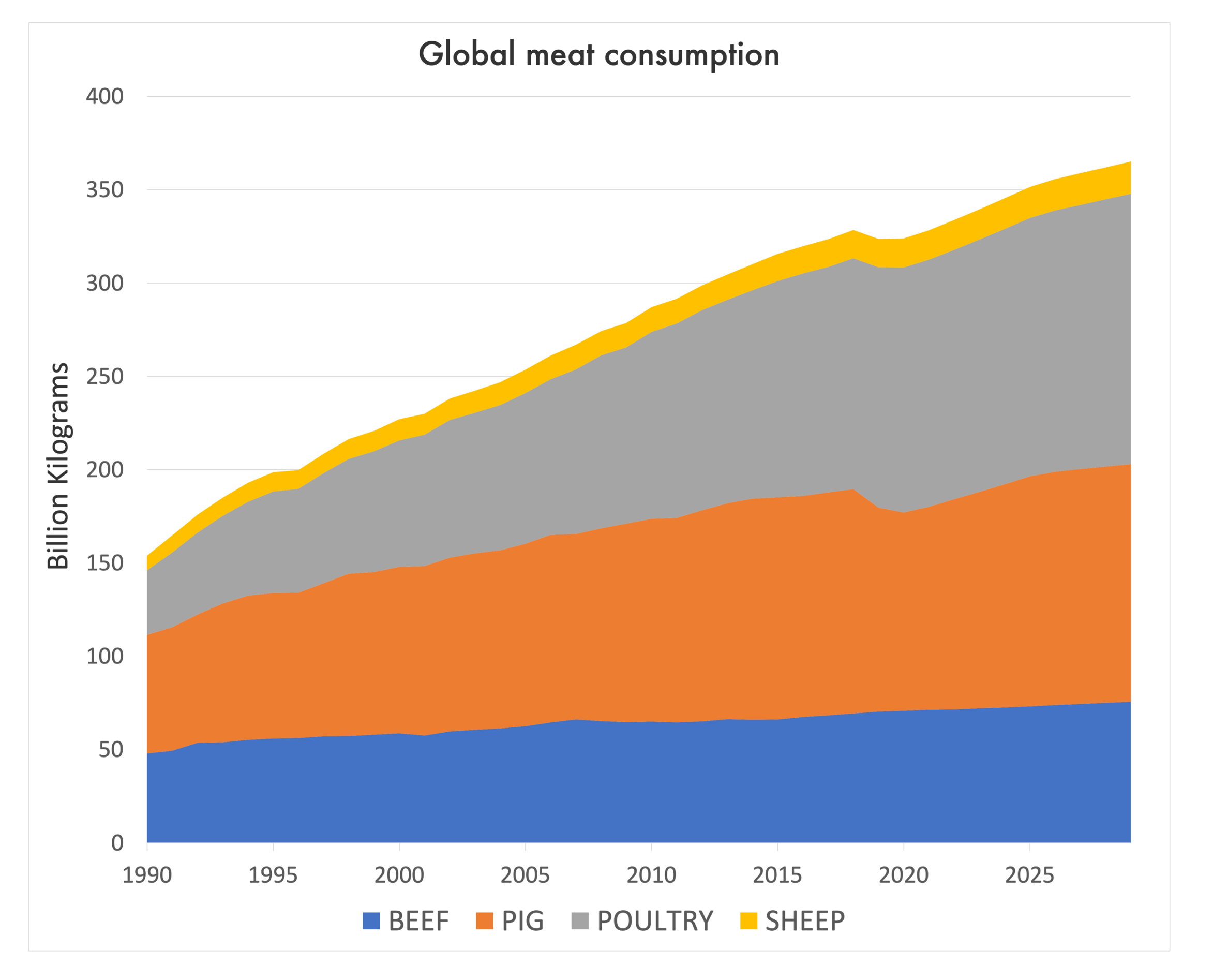

A new report by Helen at Harvard Law School, Options for a Paris-compliant livestock sector, argues that global emissions from livestock must drop by 61% by 2036 to align with the goals of the Paris Agreement. One of the authors, my colleague Matthew Hayek at NYU, is also an author of a Nature Food paper just published that criticizes the FAO’s Achieving SDG 2 without breaching the 1.5 °C threshold: A global roadmap report, arguing that the FAO doesn’t sufficiently address the shift away from the production and consumption of animal-sourced foods - particularly livestock. While the FAO report does set some milestones to reduce emissions and the growth of livestock, according to the authors of the paper, FAO doesn’t really articulate how. They also criticized FAO’s aquaculture target. FAO’s history with livestock is long and sorted. If you want to read a fascinating controversy about another report on livestock FAO produced in 2006 (Livestock’s Long Shadow), check out this piece by the Guardian. Le sigh…Can’t we all just get along?

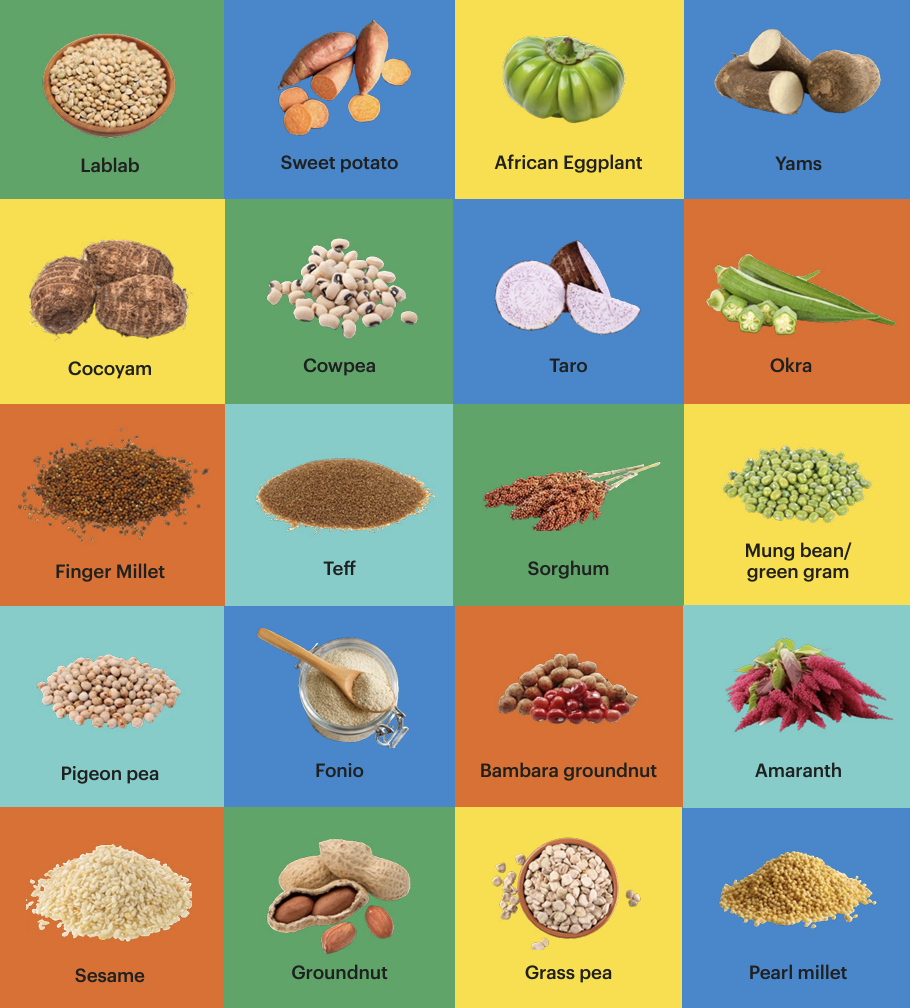

On a lighter note, and maybe less controversial food system topic (famous last words…), the Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils — also known as VACS (no, this is not a vaccine project) — a project initiated by Carey Fowler in the U.S. State Department, has released its first report and list of 20 potential crops to expand on (see figure on the left). In full disclosure, I worked with Cynthia Rosenzweig’s AgMIP team here at Columbia and NASA GISS on some of the findings. Who doesn’t love traditional, indigenous, neglected crops — now called opportunity crops — and their potential for Africa and the world? AgMIP also released an awesome dashboard called the VACS Explorer to map the resilience of these crops in the face of climate change.

Speaking of data, I am a big fan of Our World In Data’s (OWID) Hannah Ritchie, who has a new book out, Not the End of the World. I hope she’s right. I am not sure how she can muster up any positivity looking at the data - as they say, the data don’t lie!! She consistently feeds the OWID with amazing food and climate data. Her latest is on weather forecasting. She highlights their importance but also how the quality is improving to predict extreme events and trigger early warning systems better. At Columbia University’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society — also known as IRI — we have been generating these types of data for decades that serve many sectors, including agriculture, public health and energy sectors.

It is so hard to keep up with the scientific literature on food systems these days. There is just so much evidence being generated. This paper stood out a bit for me. It tries to establish a strong link between biodiversity loss and our diets. They argue, and I agree, that most eaters don’t have a clue about the potential impacts of their diets on the rich biodiversity that we are losing around the world. In the paper, they estimate the biodiversity footprint of 150 popular dishes worldwide. Of course, beef dishes have high biodiversity footprints = not good…as compared to vegetarian dishes, but there are exceptions! The authors noted that chana masala has a high biodiversity footprint. Drats. The figure below shows the top 20 dishes with the highest biodiversity footprint across three different biodiversity indicators — species richness, threatened species richness, and range rarity using different scenarios for the way food is grown/raised: a) feedlot-grown locally produced, b) feedlot-grown globally produced, c) pasture-grown locally produced, and d) pasture-grown globally produced. Plot symbols and colors represent diet and dishes’ region of origin, respectively. Ingredients in the bar chart correspond to the main ingredient in terms of weight in a dish in the top 20 dishes with the highest biodiversity footprints. Looks like green chile stew fairs a bit better than other dishes. Whew!

Top 20 biodiversity footprint dishes from around the world

A few more fun tidbits for this month’s Food Bytes. Did anyone watch the Oscars? It was pretty boring with Oppenheimer dominating, but I did notice that everyone walking the red carpet looked especially thin and fit. Celebrities are known for trying the latest fad diets and having substantive budgets for expensive trainers and personal chefs, but clearly, this was the Oscars on Ozempic. Let’s see how this all plays out, but I do fear there are reasons to be skeptical about the weight loss drug’s long-term impacts on health. As always, The Maintenance Phase podcast is spot on with its Ozempic episode. Dary Mozaffarrian, former Dean of the nutrition policy school at Tufts, wrote an interesting piece in JAMA arguing that a food-as-medicine intervention should be paired with Ozempic prescriptions. And then there is Oprah who continues to shape the conversation about weight loss and her latest journey using these GLP-1 agonist drugs.

While we are on the topic of celebrity nonsense, Erewhon (nowhere spelled backwards) is just plain silly. But celebrities and the “LA set” flock to it in droves. This piece by Kerry Howley of the Cut is so worth the read: “Erewhon’s Secrets: In the 1960s, two macrobiotic enthusiasts started a health-food sect beloved by hippies. Now it’s the most culty grocer in L.A.” The New York Times claims it’s the “hottest hangout.” Yes, this is the place where Kourtney Kardashian has branded her 'Poosh Potion Detox Smoothie’ for a cool $22 and Saba balsamic vinegar costs $50. With the fiasco of Wegmans opening in NYC (with massive queues around several blocks), let’s hope Erewhon doesn’t decide to come eastward.

Source: https://www.loe.org/shows/segments.html?programID=16-P13-00020&segmentID=5

Speaking of hippies, I have been working on a book about how America’s 1960s counterculture movement used food systems to ignite a social revolution and ultimately failed. The American counterculture movement, born during the fertile but tumultuous late 1960s to early 1970s, recognized a similar looming storm and tried to redirect its path. The mounting political, social, and cultural challenges (limitations on natural resources, industrialization, pollution, inequities, population growth) influenced an entire generation to work toward rebuilding food systems into a more ethical “ecological utopia” of balance, stability, and food consciousness. Back-to-the-land communes, food co-ops, the first Earth Day, Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog, the Black Panthers’ Breakfast Program, Cesar Chavez’s National Farm Worker’s Association, and the Diggers’ free food experiments in the Haight Ashbury were all attempts to break the status quo and democratize food systems. They approached food and environmental issues as foundations for building an ideal society while simultaneously providing nourishment and wellness for the human population and the planet. They radicalized and politicized food as a medium for social revolution. While some of their individual battles prevailed, their revolution was defeated. Why did their vision fail, and why did we not heed their canary calls when we still had a fighting chance to fix the system? This story is about the short-lived influence of the counterculture hippie movement, why they clung to food and environment as their raison d’etre, and why we’re still fascinated by their history but struggle to learn from it in these darker, more dangerous times. So, stay tuned as I continue to scroll away.

Reminds me of one of the Sound Furies song’s we recorded a few years ago, V-Dubbed.

in the back of a ’66 VW

for a last cigarette can i bug u?

in her birthday suit under the trenchcoat

Patty Hearst doubled as her scapegoat